Comparative Analysis of Desert Locust Situations in Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, South Sudan, and Chad: January 2024 Overview

Background

The Desert Locust (Schistocerca gregaria) is one of the most destructive migratory pests in the world, capable of causing extensive damage to crops and pastures. The dynamics of locust populations are closely linked to weather conditions, and their management requires constant monitoring and timely control measures. This comparative analysis focuses on the locust situation in Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, South Sudan, and Chad, as reported in the Desert Locust Bulletin No. 544 for January 2024.

Introduction

In January 2024, the Desert Locust situation varied significantly across the countries, as mentioned earlier, reflecting differences in ecological conditions, the effectiveness of control measures, and locust development stages. This analysis aims to compare these countries’ locust situations, highlighting the unique challenges and responses. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for improving locust management strategies and mitigating the impact on food security and livelihoods.

Comparative Analysis

Egypt: The first winter generation of locusts continued along the southeast Red Sea coast, with groups and swarms of immature and mature adults observed in various areas, including El Sheikh El Shazly and Halaib. Late instar hopper groups and bands had fledged by the end of the third week, with copulating and egg-laying observed towards the end of the month. Control operations covered 8,657 hectares. The forecast for February indicates the hatching of the second generation, with hopper groups and bands expected throughout the month and new immature adults likely to appear by mid-March.

Eritrea: January saw the continuation of the first winter generation along the central and northern Red Sea coast. The situation involved groups and some swarms of immature and mature adults, with significant control operations treating 14,594 hectares. The second generation is expected to bring continued hopper groups and bands, with fledgling and the emergence of new immature adults anticipated post-mid-February. Control measures and environmental conditions are likely to reduce locust numbers by mid-March.

Ethiopia: A very small immature swarm was reported near Dire Dawa in January, marking a relatively minor locust presence compared to neighboring countries. The limited data suggests minimal locust activity during the period.

South Sudan: The document does not provide specific data for South Sudan. Given its proximity to affected regions, vigilance and monitoring are essential to prevent potential incursions.

Chad: There were no locust reports in January, and no significant developments are expected. This suggests that Chad experienced a calm locust situation during this period, likely due to unfavorable breeding conditions for locusts in the region.

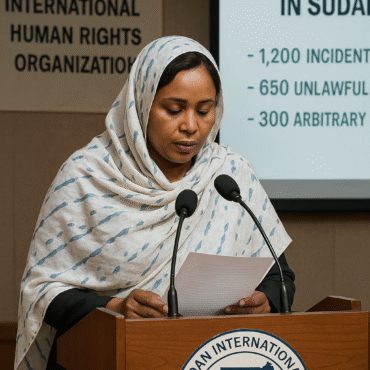

Sudan: The first winter generation persisted along the Red Sea coast, with a mix of immature and mature groups and many small swarms reported. Control operations were extensive, covering 38,736 hectares. The forecast suggests the continuation of the second generation with hopper groups and bands and a decrease in locust numbers post-mid-March due to control efforts and environmental factors.

Conclusion

The locust situation in January 2024 showed significant variability across Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, South Sudan, and Chad. While Egypt and Eritrea faced more severe challenges with active generations and extensive control operations, Ethiopia and Chad reported minimal or no locust activity. Sudan also experienced a significant locust presence but managed to undertake substantial control measures. These variations underscore the importance of tailored strategies and regional cooperation in locust management to safeguard agriculture and food security in affected areas.

Add Comment